TL;DR: You can get better performance, fewer issues over time, and the fun of DYI by making your own router from an older computer.arstechnica.com wrote:I've noticed a trend lately. Rather than replacing a router when it literally stops working, I've needed to act earlier—swapping in new gear because an old router could no longer keep up with increasing Internet speeds available in the area. (Note, I am duly thankful for this problem.) As the latest example, a whole bunch of Netgear ProSafe 318G routers failed me for the last time as small businesses have upgraded from 1.5-9mbps traditional T1 connections to 50mbps coax (cable).

Yes, coax—not fiber. Even coax has proved too much for the old ProSafe series. These devices didn't just fail to keep up, they fell flat on their faces. Frequently, the old routers dropped speed test results from 9mbps with the old connection to 3mbps or less with the 50mbps connection. Obviously, that doesn't fly.

These days, the answer increasingly seems to be wireless routers. These tend to be long on slick-looking plastic and brightly colored Web interfaces but short on technical features and reliability. What's a mercenary sysadmin to do? Well, at its core, anything with two physical network interfaces can be a router. And today, there are lots and lots of relatively fast, inexpensive, and (super important!) fully solid-state generic boxes out there.

So, the time had finally come. Faced with aging hardware and new consumer offerings that didn't meet my needs, I decided to build my own router. And if today's morphing connectivity landscape leaves you in a similar position, it turns out that both the building and the build are quite fast.

Why do it the hard way

A lot of you are probably muttering, "right, pfSense, sure." Some of you might even be thinking about smoothwall or untangle NG. I played with most of the firewall distros out there, but I decided to go more basic, more old school: a plain, CLI-only install of Ubuntu Server and a few iptables rules.

Admittedly, this likely isn't the most practical approach for every reader, but it made sense for me. I have quite a bit of experience finessing iptables and the Linux kernel itself for high throughput at Internet scale, and the fewer shiny features and graphics and clicky things that are put between me and the firewall table, the less fluff I have to get out of the way and the fewer new not-applicable-in-the-rest-of-my-work things I have to learn. Any rule I already know how to create in iptables to manage access to my servers, I also know how to apply to my firewall—if my firewall's running the same distro as my servers are.

Also, I work pretty heavily with OpenVPN, and I want to be able to continue setting up both its servers and clients in the way I already rely on. Some firewall distros have OpenVPN support built in and some do not, but even the ones with built-ins tend to expect things to run differently than I do. Again, the more the system stays out of my way, the happier I'll be.

As an additional bonus, I know that I can very easily keep everything completely up to date on my new and completely vanilla Ubuntu router. It's all supported directly by Canonical, and it can (and does) all have automatic updates turned on. Add the occasional cron job to reboot the router (to get new kernels), and I'm golden.

Hardware, hardware, hardware

We'll go through the how-to in a future piece, but today it's important to establish why a DIY router-build may be the best option. To do that, you first need to understand today's general landscape.

In the consumer world, routers mostly have itty-bitty little MIPS CPUs under the hood without a whole lot of RAM (to put it mildly). These routers largely differentiate themselves from one another based on the interface: How shiny is it? How many technical features does it have? Can users figure it out easily?

At the higher end of the SOHO market, you start seeing some smartphone-grade ARM CPUs and a lot more RAM. These routers—like the Nightgear Nighthawk series, one of which we'll be hammering on later—feature multiple cores, higher clock speeds, and a whole lot more RAM. They also feature much higher price tags than the cheaper competition. I picked up a Linksys EA2750 for $89, but the Netgear Nighthawk X6 I got with it was nearly three times more expensive (even on holiday sale!) at $249.

Still, I wanted to go a different route. A lot of interesting and reasonably inexpensive little x86-64 fanless machines have started showing up on the market lately. The trick for building a router is finding one with multiple NICs. You can find a couple of fairly safe bets on Amazon, but they're older Atom-based processors, and I wanted a newer Celeron. After some good old-fashioned Internet scouring and dithering, finally I took the Alibaba plunge and ordered myself a new Partaker Mini PC from Shenzhen Inctel Technology Company. After $240 for the router itself and another $48 for a 120GB Kingston SSD from Newegg, I'd spent about $40 more on the Homebrew Special than I had on the Nighthawk. Would it be worth it?

A challenger appears

Before we get testing started, let's take a quick visual look at the competitors.

That Nighthawk is, by comparison to the others, HUGE and imposing (even more so than the picture makes it appear). It's actually significantly larger than my Homebrew Special, which is a fully functional, general purpose PC you could use as a perfectly competent desktop. It's like DC Comics asked H.R. Giger to lend a hand designing a wireless router for Batman.

The Homebrew Special itself is kinda adorable. It has one blue and one red LED inside the case, and at night, the light from both spills out of its cooling vents indirectly, giving the network stack a festive party look. If there were any fans to cause a flickering it would drive me insane, but since it's a steady-state soft glow, I actually like it.

The Linksys and the Buffalo, on the other hand, look like exactly what they are—cheap routers. However, it's worth noting the styling on the Linksys is a big improvement over the brand's past. It looks more like something professional and less like a children's toy. (But enough about the styling—it's time to put these poor routers through the gauntlet.)

The obvious first challenge is a simple bandwidth test. You put one computer on the LAN side and one computer on the WAN side, and you run a nifty little tool called iperf through the middle. Simple, right?

Well, that would make for a short, boring article. The network itself measures gigabit, the three gigabit routers measure gigabit, and the 100 megabit router measures 100 megabit.

In actuality, a test this simple doesn't even begin to tell the story. The only reason to do it may be to show how pointless it is. Router manufacturers are becoming more aware that people actually test their product, and no manufacturer wants its product to be anywhere but the top of something like smallnetbuilder's router chart. In light, manufacturers are actively chasing stats these days.

The problem is, stats are just stats. Being able to hit a high number on a pure throughput test is better than nothing, but it's a far cry from the whole story. I learned that lesson the hard way while working for a T-1 vendor in the early 2000s. Their extremely expensive Adtran modems could handle 50 to 100 people's normal Internet usage just fine, but a single user running Limewire or some other P2P client would bring the whole thing down in a heartbeat. (The fix back then: put an inexpensive-but-awesome $150 Netopia router in front of that expensive Adtran modem. Problem solved.)

Even for relatively simple routing—no deep packet inspection, no streaming malware scanning or intrusion detection, no shaping—the CPU and the RAM available to the router are both important well above and beyond the ability to saturate the Internet link. Peer-to-peer filesharing is about the most brutal activity a network will see, these days (whether it's bittorrent, one of the Gnutella or eDonkey variants, or a game company's peer-to-peer download system). I was done playing WoW by the time Blizzard's P2P distribution system was introduced, but my roommate at the time wasn't. On its launch day, the new WoW peer download system unhelpfully defaulted to no throttling whatsoever. It cheerfully tried to find and maintain connections with literally thousands of clients simultaneously, and my home network went down like Gilbert Godfried getting tackled by Terry Tate. My roommate and I had words.

Based on such past experience, I don't just want to minimally "test" my challengers and call it a day, I want to really make them sweat. So to do that, I'm going to hit them with workloads that stress three problem areas: saturating the network link, making and breaking individual TCP/IP connections really quickly, and holding massive numbers of individual TCP/IP connections open at the same time.

GEAR & GADGETS / PRODUCT NEWS & REVIEWS

Numbers don’t lie—it’s time to build your own router

With more speed available and hardware that can't adapt, DIY builds offer peak performance.

by Jim Salter - Jan 19, 2016 7:00am PST

Share Tweet Email

330

I've noticed a trend lately. Rather than replacing a router when it literally stops working, I've needed to act earlier—swapping in new gear because an old router could no longer keep up with increasing Internet speeds available in the area. (Note, I am duly thankful for this problem.) As the latest example, a whole bunch of Netgear ProSafe 318G routers failed me for the last time as small businesses have upgraded from 1.5-9mbps traditional T1 connections to 50mbps coax (cable).

Yes, coax—not fiber. Even coax has proved too much for the old ProSafe series. These devices didn't just fail to keep up, they fell flat on their faces. Frequently, the old routers dropped speed test results from 9mbps with the old connection to 3mbps or less with the 50mbps connection. Obviously, that doesn't fly.

These days, the answer increasingly seems to be wireless routers. These tend to be long on slick-looking plastic and brightly colored Web interfaces but short on technical features and reliability. What's a mercenary sysadmin to do? Well, at its core, anything with two physical network interfaces can be a router. And today, there are lots and lots of relatively fast, inexpensive, and (super important!) fully solid-state generic boxes out there.

So, the time had finally come. Faced with aging hardware and new consumer offerings that didn't meet my needs, I decided to build my own router. And if today's morphing connectivity landscape leaves you in a similar position, it turns out that both the building and the build are quite fast.

Why do it the hard way

A lot of you are probably muttering, "right, pfSense, sure." Some of you might even be thinking about smoothwall or untangle NG. I played with most of the firewall distros out there, but I decided to go more basic, more old school: a plain, CLI-only install of Ubuntu Server and a few iptables rules.

Admittedly, this likely isn't the most practical approach for every reader, but it made sense for me. I have quite a bit of experience finessing iptables and the Linux kernel itself for high throughput at Internet scale, and the fewer shiny features and graphics and clicky things that are put between me and the firewall table, the less fluff I have to get out of the way and the fewer new not-applicable-in-the-rest-of-my-work things I have to learn. Any rule I already know how to create in iptables to manage access to my servers, I also know how to apply to my firewall—if my firewall's running the same distro as my servers are.

Enlarge / Behold, a Unix beard.

Also, I work pretty heavily with OpenVPN, and I want to be able to continue setting up both its servers and clients in the way I already rely on. Some firewall distros have OpenVPN support built in and some do not, but even the ones with built-ins tend to expect things to run differently than I do. Again, the more the system stays out of my way, the happier I'll be.

As an additional bonus, I know that I can very easily keep everything completely up to date on my new and completely vanilla Ubuntu router. It's all supported directly by Canonical, and it can (and does) all have automatic updates turned on. Add the occasional cron job to reboot the router (to get new kernels), and I'm golden.

Hardware, hardware, hardware

We'll go through the how-to in a future piece, but today it's important to establish why a DIY router-build may be the best option. To do that, you first need to understand today's general landscape.

In the consumer world, routers mostly have itty-bitty little MIPS CPUs under the hood without a whole lot of RAM (to put it mildly). These routers largely differentiate themselves from one another based on the interface: How shiny is it? How many technical features does it have? Can users figure it out easily?

At the higher end of the SOHO market, you start seeing some smartphone-grade ARM CPUs and a lot more RAM. These routers—like the Nightgear Nighthawk series, one of which we'll be hammering on later—feature multiple cores, higher clock speeds, and a whole lot more RAM. They also feature much higher price tags than the cheaper competition. I picked up a Linksys EA2750 for $89, but the Netgear Nighthawk X6 I got with it was nearly three times more expensive (even on holiday sale!) at $249.

Enlarge / Don't judge me—I was hungry.

Still, I wanted to go a different route. A lot of interesting and reasonably inexpensive little x86-64 fanless machines have started showing up on the market lately. The trick for building a router is finding one with multiple NICs. You can find a couple of fairly safe bets on Amazon, but they're older Atom-based processors, and I wanted a newer Celeron. After some good old-fashioned Internet scouring and dithering, finally I took the Alibaba plunge and ordered myself a new Partaker Mini PC from Shenzhen Inctel Technology Company. After $240 for the router itself and another $48 for a 120GB Kingston SSD from Newegg, I'd spent about $40 more on the Homebrew Special than I had on the Nighthawk. Would it be worth it?

A challenger appears

Before we get testing started, let's take a quick visual look at the competitors.

Enlarge / Clockwise from the far left: 1. the Ubuntu-powered Homebrew Special, 2. the Netgear Nighthawk X6, 3. the Buffalo WHR-G300N-v2, and 4. the Linksys N600 EA-2750. Far right, looming over them all: Monolith, one of the two servers used for testing.

That Nighthawk is, by comparison to the others, HUGE and imposing (even more so than the picture makes it appear). It's actually significantly larger than my Homebrew Special, which is a fully functional, general purpose PC you could use as a perfectly competent desktop. It's like DC Comics asked H.R. Giger to lend a hand designing a wireless router for Batman.

The Homebrew Special itself is kinda adorable. It has one blue and one red LED inside the case, and at night, the light from both spills out of its cooling vents indirectly, giving the network stack a festive party look. If there were any fans to cause a flickering it would drive me insane, but since it's a steady-state soft glow, I actually like it.

The Homebrew Special—looking a bit blurry, because I wanted to take a low-light shot to try to capture the disco glow.

EXPAND GALLERY TO FULL SIZE

The Linksys and the Buffalo, on the other hand, look like exactly what they are—cheap routers. However, it's worth noting the styling on the Linksys is a big improvement over the brand's past. It looks more like something professional and less like a children's toy. (But enough about the styling—it's time to put these poor routers through the gauntlet.)

The obvious first challenge is a simple bandwidth test. You put one computer on the LAN side and one computer on the WAN side, and you run a nifty little tool called iperf through the middle. Simple, right?

Enlarge / Not pictured: interesting results.

Well, that would make for a short, boring article. The network itself measures gigabit, the three gigabit routers measure gigabit, and the 100 megabit router measures 100 megabit.

In actuality, a test this simple doesn't even begin to tell the story. The only reason to do it may be to show how pointless it is. Router manufacturers are becoming more aware that people actually test their product, and no manufacturer wants its product to be anywhere but the top of something like smallnetbuilder's router chart. In light, manufacturers are actively chasing stats these days.

The problem is, stats are just stats. Being able to hit a high number on a pure throughput test is better than nothing, but it's a far cry from the whole story. I learned that lesson the hard way while working for a T-1 vendor in the early 2000s. Their extremely expensive Adtran modems could handle 50 to 100 people's normal Internet usage just fine, but a single user running Limewire or some other P2P client would bring the whole thing down in a heartbeat. (The fix back then: put an inexpensive-but-awesome $150 Netopia router in front of that expensive Adtran modem. Problem solved.)

Even for relatively simple routing—no deep packet inspection, no streaming malware scanning or intrusion detection, no shaping—the CPU and the RAM available to the router are both important well above and beyond the ability to saturate the Internet link. Peer-to-peer filesharing is about the most brutal activity a network will see, these days (whether it's bittorrent, one of the Gnutella or eDonkey variants, or a game company's peer-to-peer download system). I was done playing WoW by the time Blizzard's P2P distribution system was introduced, but my roommate at the time wasn't. On its launch day, the new WoW peer download system unhelpfully defaulted to no throttling whatsoever. It cheerfully tried to find and maintain connections with literally thousands of clients simultaneously, and my home network went down like Gilbert Godfried getting tackled by Terry Tate. My roommate and I had words.

Based on such past experience, I don't just want to minimally "test" my challengers and call it a day, I want to really make them sweat. So to do that, I'm going to hit them with workloads that stress three problem areas: saturating the network link, making and breaking individual TCP/IP connections really quickly, and holding massive numbers of individual TCP/IP connections open at the same time.

I've got a botnet in my pocket, and I'm ready to rock it

I briefly considered setting up some kind of hideous, Docker-powered monstrosity with tens of thousands of Linux containers with individual IP addresses, all clamoring for connections and/or serving up webpages. Then I came to my senses. As far as the routers are concerned, there's no difference between maintaining connections to thousands of individual IP addresses or just to thousands of ports on the same IP address. I spent a little bit of time turning Lee Hutchinson's favorite webserver nginx into a ridiculous Lovecraftian monster with 10,000 heads and an appetite for destruction.

For each router, I used ApacheBench to test downloading a jpeg with three different file sizes (10K, 100K, and 1M) at four different concurrency levels (10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 simultaneous clients). This gives us 12 tests in total, not counting our initial iperf test, and it's worth seeing them all as a sort of spectrum.

In most respects, that 10K file is more challenging. The small file size means you can deliver a lot more of the individual files every second before you saturate the interface, which means making and breaking a lot more TCP connections, which is taxing for the router's CPU. On the other hand, the 1M file means you're guaranteed to be keeping more connections open on the higher concurrency levels. It's worth seeing how the routers handle the entire spectrum, because each level does a fairly decent job of modeling a fairly common challenge a router might need to handle (downloading or sending a large number of e-mails, handling peer-to-peer file sharing, or general Web browsing from a lot of users) if taken to an extreme level.

Ultimately, I ended up needing to not only tune nginx, but the Linux kernel itself, in order to reliably deliver the kind of throughput I was looking for. The routers themselves are "stock"—even my Homebrew Special was left untuned—but the test servers, Menhir, and Monolith (each with AMD FX-8320 8-core CPU, 32GB DDR3 RAM, and Ubuntu Trusty OS patched completely up to date) needed some fairly serious massaging in order to handle that kind of load.

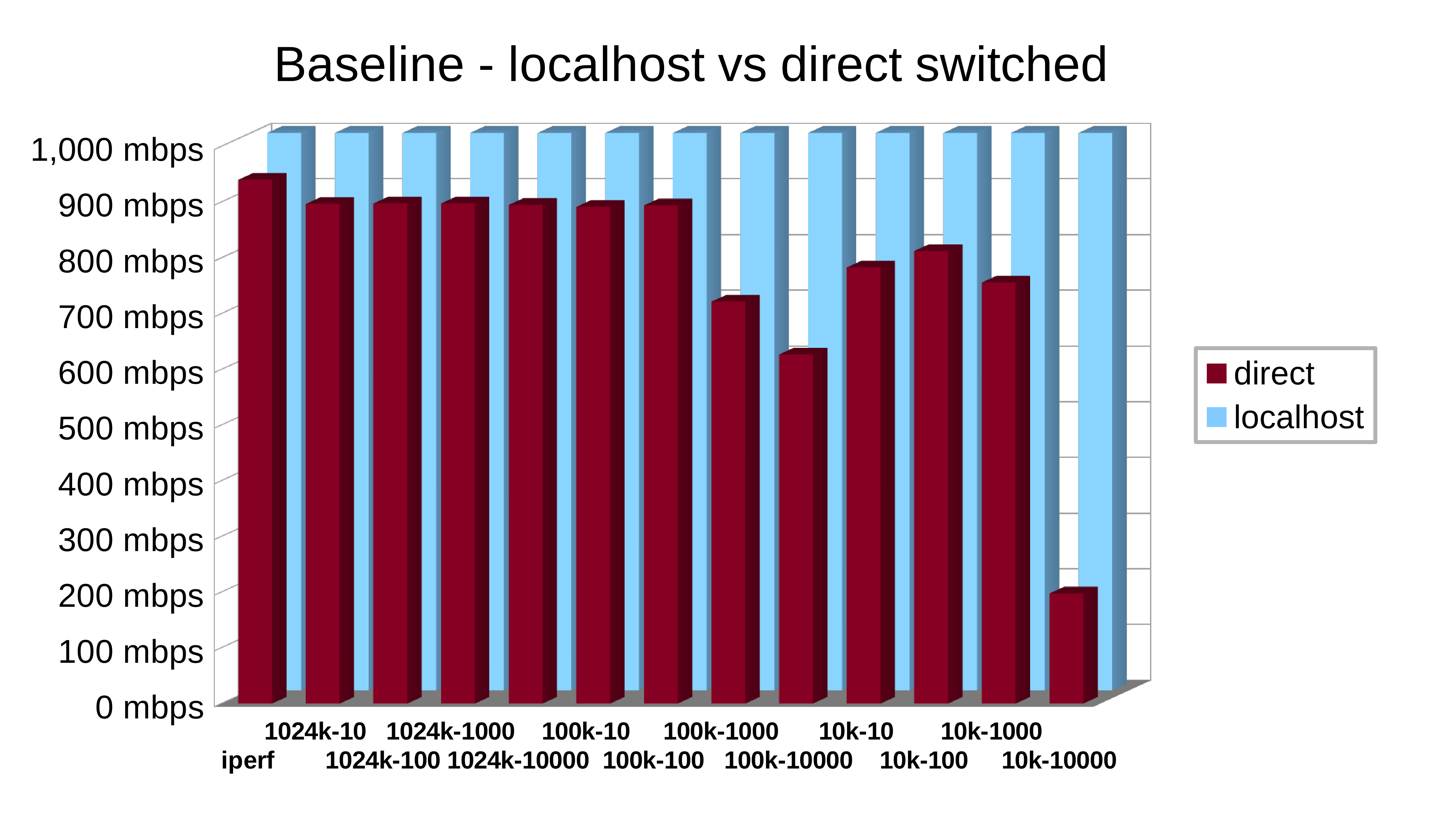

With that much craziness, you want to make sure of what your actual servers and network are capable of before jumping to any conclusions about routers you put between them. To start, I first tested Menhir by itself on the localhost interface (no network at all) and then tested between the servers across my network switch only (a Netgear ProSafe 16-port gigabit, in case you're wondering).

The localhost results couldn't have been better—far, far higher throughput than gigabit for every test. In fact, I had to manually limit the scale of the graph's Y axis or you'd have trouble seeing the real tests at all. The direct network test wasn't too bad, but we're obviously starting to hit some limits at the upper end. I'm not sure whether the struggling component is the switch itself or the onboard network interfaces in both servers, but something isn't completely up to the challenge. It's good enough to work with, though. Time to finally engage the routers.

Let's get ready to rumble!

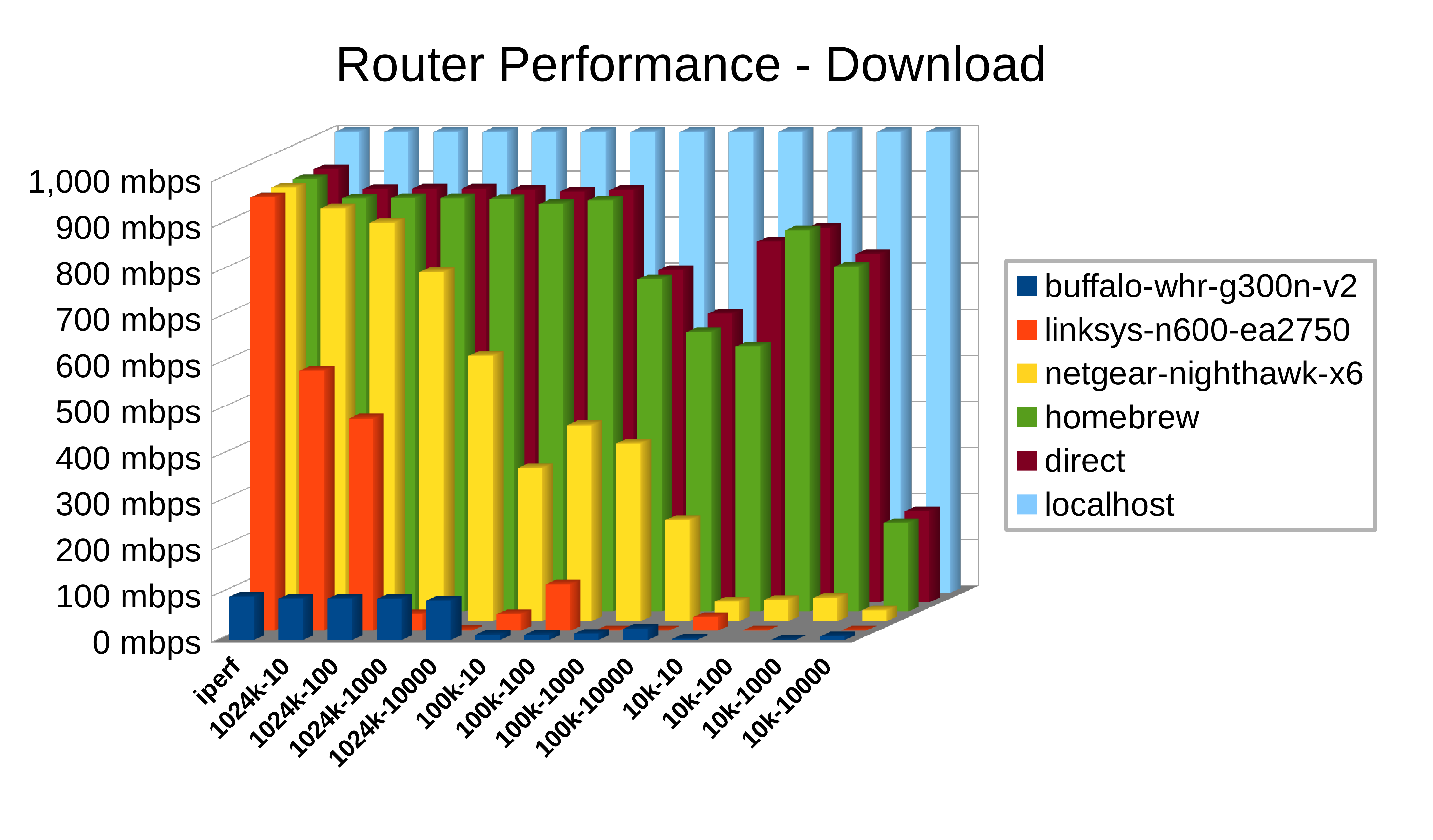

I was a little nervous. I already felt pretty affectionate about my little homebrew device—after all, I built it myself. I knew it would easily dominate the elderly Buffalo I dug out of a drawer and the Linksys, which was literally the cheapest thing at Staples with a gigabit interface. But could it beat that laser-guided atomic steamhammer of a Nighthawk? I thought so, but I wasn't sure.

When the download tests were finished, there were no more questions about the Homebrew Special. Yes, it could beat the Nighthawk... and walk away yawning afterward. Aside from one small dip at the 10K file size/10 concurrent connections level (which challenges the CPU with the absolute most made-and-broken connections), it performed almost identically to the direct network connection itself.

The Nighthawk, incidentally, really is a great SOHO router I have deployed quite a lot of. However, it fell off almost immediately. For megabyte downloads 10 at a time, it was neck-and-neck. With any more of a challenge, performance started sloping off sharply.

The Linksys, no surprise, did not perform well at all. Even a task as simple as downloading 10 files at the same time cut its throughput to almost half of what the naive iperf test showed. Things only got worse from there, and it failed to even complete several tests. On the plus side, the Linksys does a fine job of demonstrating that your router really does matter.

Finally, the valiant little Buffalo deserves some shout-out. Despite costing less than the Linksys when it was brand new (eight years ago, mind you) and languishing in a desk drawer for five years, it came off the proverbial bar stool and actually beat the Linksys in half of the tests. The Buffalo had that success despite a network interface that was rated for a tenth the speed. That's moxie. The next time somebody takes a cheap stab at fresh-off-the-boat Chinese-made products, I'm going to shout "Remember the Buffalo!"

Before coming to any conclusions, however, upload speeds need to be accounted for.

Luckily, nothing has really changed about the relationships between the routers here. The Homebrew still looks like it's not even there, almost completely matching a direct network connection. The Nighthawk continues to utterly dominate the Linksys, and the scrappy little Buffalo is still doing its obsolete best. In absolute terms, you can see that both the Nighthawk and the Linksys are doing slightly better on upload than they were on download, but it's nothing to write home about. This bottom line remains the same: the Homebrew Special keeps up with the network (oddly, even doing better than a direct connection in the 10,000 connection/10K file test), the Nighthawk is clearly worth its price tag compared to the Linksys, and the Linksys is, well, inexpensive.

With this final graph, we do have a new set of results, though—the salmon-colored bars, which are pretty steady at a bit over 200mbps across the graph. That's the Homebrew Special flexing its crypto muscle. It has an OpenVPN server running. For that test, the WAN-side server, Menhir, is connected to the router's on-board OpenVPN server. Traffic for the LAN side of the Homebrew Special is routed across the VPN tunnel, so Menhir is hitting the LAN IP address of Monolith (the LAN-side server) by way of some pretty impressive 2048-bit, SSL-based encryption. Given that nobody's offering any Internet connections over 200mbps in my area yet, that makes my inner crypto nerd dance with glee. I could literally encrypt every single byte of my Internet traffic, in either direction, without a performance penalty.

One quick closing caveat

As impressive as my little Homebrew Special is, there's one thing it's missing, which all three other contestants offer: wireless access. I could add a wireless card to the Homebrew and make it serve up wireless, but currently I have no plans to. I am all too familiar with what's available for PC wireless cards, and they all stink on ice. Even cheap devices like the Linksys or the Buffalo would deliver a smackdown for wireless coverage and range, and the Nighthawk isn't even in the same league. It really is a laser-guided atomic steamhammer when it comes to wireless range, coverage, and simultaneous connectivity. (I have one of them covering 50+ users in a 53,000-square-foot facility from corner to corner right now.)

With that said, nothing stops you from using a separate WAP (Wireless Access Point) strictly to handle Wi-Fi duties. In my house, that's a pair of Ubiquiti "hockey puck" WAPs, one for each floor of the house. They're a bit more work to manage than the Nighthawk, but the pair of them costs half as much. They're pretty standard Linux devices that can be SSH'ed directly into and are managed from a pretty cool little Web application that you can run... you guessed it, directly on the Homebrew Special. (Migrating the Ubiquiti Server from my workstation to the Homebrew Special will be one of my first tasks after this piece, and I'll then promote it to active use in front of my home office network.)

In the name of thoroughness, we should observe one shared limitation, something by all the consumer network gear I've ever managed: the desire to reboot after almost any change. Some of those reboots take well over a minute. I haven't got the foggiest idea why, but whatever the reason, the Homebrew Special isn't afflicted with this industry standard. You make a change, you apply it, you're done. And if you do need to reboot the Special? It's up again in 12 seconds. (I timed it by counting dropped pings.)

So if the numbers have swayed you, and you want to build your own Homebrew Special, all it takes is a PC with two physical network interfaces. That can be a special mini PC like the one I used here, or it can be any old box you've got lying around that you can cram two network cards into. Don't let the first screenshot intimidate you. Building your own truly fast router isn't that hard to get the hang of. And if you're clamoring for a roadmap, in fact, we'll outline the process all the way from "here is a regular computer" to "here is a router, and here's how you configure it" soon.

Personally, I'd go with Gentoo, since that's an old favorite of mine for both making servers and workstations, but of course you don't have to. Basically, setting up an older computer with two (or more) network cards, installing Linux on it, and then configuring it as the author did in the article is much less difficult or time consuming as you might think.

Moreover, you also get to feel more involved in your home's internet access without all that much risk. It's actually simpler to do than making a new gaming workstation - not that this should be too much of a surprise, but still.